Again, it’s a bit different…

I’m writing this blog post again with a bit of a different lens. It’s following on from the previous post about the occupational nature of matrescence – taking a lifespan perspective – shifting our focus to understand how we contextualise our practices supporting mothers and birthing people during perinatal transitions.

I’m feeling motivated to do this after getting some feedback this week that textbooks are intimating for a lot of people – and that the knowledge translation goal for me is super important. This one ended up being be a bit of longer post – which I hope isn’t a deterrent! Anyway, here goes… 🙂

So, again, we know the perinatal period is often treated as a short, clinical window of time, bracketed by birth statistics and developmental outcomes, and postnatal checklists. I want to make it clear that I’m not dismissing the importance of these – medical advancements have absolutely revolutionised options and outcomes associated with fertility and birth in many incredible ways – and I, for one, certainly wouldn’t be alive without them! Of course they’re not perfect, and – irrespective of funding – women within these systems definitely have needs which could be better met with full MDT input, including OTs.

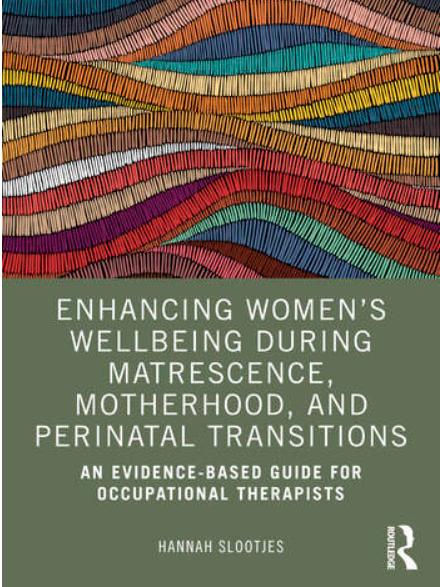

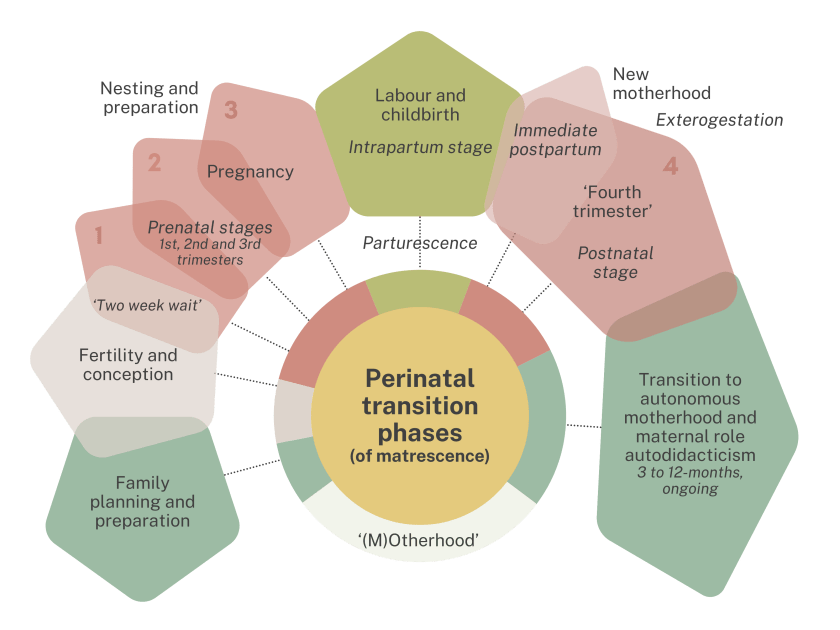

Internationally, OTs are practicing with clients during the perinatal period, and we’re bringing our own unique lens to understanding needs and challenges during this transitional phase (my PhD research are findings represented by illustrative interpretation in Figure 17).

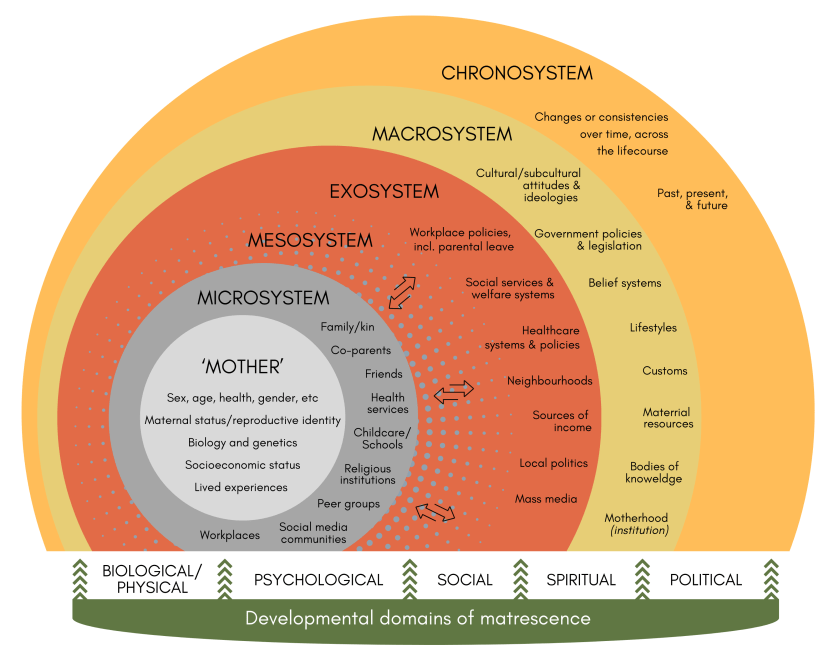

Reflecting on feedback I received about the Person-centred Occupational Model of Matrescence (POMM) (see Figure 17 from my PhD thesis below) – which mapped how occupational therapists can support women and families through these transformative phases by recognising the ecological, cultural, and deeply human dimensions of mother-becoming – it seemed important to really break down what this meant for OTs who were working with mothers during perinatal transitions.

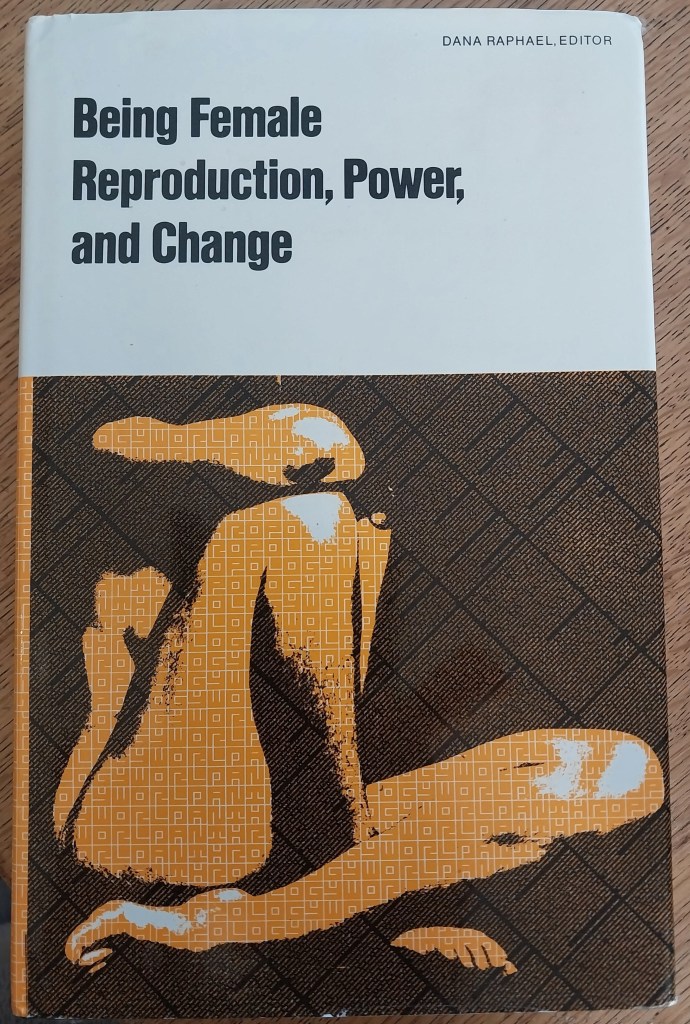

After completing my PhD, I was lucky and privileged enough to have the space and opportunity to explore this further in a textbook chapter, The Perinatal Transitions of Matrescence: An Occupational Therapy Perspective (Slootjes, 2025). When we zoom out through a person-centred occupational lens, the perinatal period looks a bit different. From this perspective, the perinatal period is not a single event but a fluid series of transitions nested within the larger journey of matrescence (the ongoing, lifelong process of becoming [or not becoming, or even letting go of being] a mother).

Seeing the perinatal period as rite of transition, not timeline

While the POMM doesn’t feature much in the textbook, Figure 10.1 – A rite of transition: The chronological pathways, milestones, stages, and phases of perinatal transitions – continues developing the idea that perinatal period is non-lineal and a continuum. This was developed to reflect what we see as OTs when we support someone through perinatal transitions, backed by evidence-based concepts in scientific literature.

It’s the lens that shapes our worldview for a certain time during matrescence (illustrated in Figure 17 of the POMM), and is characterised by so many occupational factors relating to loss, hope, fear, dread, gain, progress, and set-backs, expectations, circumstance, choice, recovery, healing and responsibility.

These can occur during any phase, from family planning and conception through pregnancy, labour, postpartum recovery, the early experiences of motherhood, and the period thereafter where mothering occupations shift to a more autodidactic phase. Each phase carries its own occupations, milestones, and rituals: nesting, preparing, birthing, healing, adjusting, learning, letting go.

This framing invites us to think less about rigid concepts of step-by-step “stages” and more about how individuals move through, circle back, or diverge from these transitions in their own time and way. Some pathways are linear, others are interrupted, cyclical, or nonlinear – either by choice or circumstances outside of control. Each tells a story about hope, fear, anticipation, resilience, identity, and adaptation.

Occupational therapy brings language to these lived experiences – recognising that having, doing, being, becoming, belonging, and interacting are central to how mothers navigate these phases (Slootjes, 2022). It’s a trick, really, because – as OTs – this kind of approach doesn’t fit neatly into existing maternity care services where there’s rarely funding for full allied health teams. But we do have a lot to offer the women who need our help. Many of us are responding by shifting into private practice to increase our availability for perinatal clients, and things will undoubtedly change as the evidence base for our services grows.

A rite of transition, not just a healthcare event

Across cultures, childbirth has always carried ritual significance – acts of protection, preparation, and communal care. In modern healthcare, many of these rituals have been replaced by routines: Discharge summaries, feeding schedules, medical follow-ups (Davis-Floyd, 2022). However, as Grimes (2000) reminded us, humans have a deep need to ritualise transformation.

Occupational therapists see rituals as meaningful occupations – the gestures that help women situate themselves within change. Lighting a candle before birth, crafting a nursery or nesting, giving gifts, writing a reflection after miscarriage, or sharing a baby’s “firsts” with community – each of these acts holds the power to integrate experience and identity.

When services make space for ritual and reflection, not just medical monitoring, the perinatal period becomes opportunity for supported rite of transition or a rite of passage – depending on the birthing person’s unique positionality and culture, and circumstances.

The five developmental domains in practice

During perinatal transitions, mothers experience changes across five developmental domains, all dynamically interacting within their ecological context:

- Biological/physical: Transformation of the body’s systems and functions, affecting movement, sensation, energy, and participation.

- Psychological: Emotional regulation, identity formation, neurobiological and cognitive shifts.

- Social:/psychosocial Relationships, role negotiation, community expectations, and the occupational reorganisation of daily life.

- Spiritual: meaning-making, belonging, and connection to something larger than oneself.

- Political: the influence of policies, funding, safety, and social structures on how mothering is lived and valued.

From this view, perinatal care is not just about health, it’s about human development, wellbeing, quality of life, occupational adaption, and changing identities, roles, and routines, healthy relationships – and so much more.

When healthcare becomes holistic

The bioecological lens shared in the previous post about matrescence (Figure 7.1) helps us see how each mother’s experience is shaped by the systems surrounding her – the micro-level of family and co-parents, the meso-level of connected services and communities, the exo-level of workplace and policy environments, and the macro-level of cultural and ideological forces.

Occupational therapists can help bridge these levels, advocating for policies that protect perinatal wellbeing and designing services that honour women’s autonomy, rituals, and lived realities.

Imagine perinatal care that makes room for stories, spirituality, and agency alongside safety, science, and skill. That is what it means to move from “perinatal management” toward perinatal transition support. Things are definitely changing, and the OT workforce are gearing up and to get ready for the opportunities that are coming!

Questions we can ask ourselves as a reflection to guide future practice

- What would it look like if we all treated the perinatal period as a rite of transition, rather than a clinical event?

- How might we hold space for mother’s having positive experiences having, doing, being, becoming, belonging, and interacting during perinatal transitions, beyond focusing to ‘treat’ medical issues?

- And how might we design care, education, and policy that reflect the full ecology of matrescence rather than just its medical margins?

Because the perinatal period does not define mother-becoming, and also is not the beginning or end of matrescence – it’s one incredible point of transition (and sometimes transformation) along the way. What do you think?

Key references

Davis-Floyd, R. (2022). Birth as an American rite of passage (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/978100300139

Grimes, R. L. (2000). Deeply into the bone: Re-inventing rites of passage. University of California Press.

Slootjes, H. (2022). The Role of Occupational Therapists in Perinatal Health [Doctoral thesis, La Trobe University]. Open Access at La Trobe (OPAL). https://doi.org/10.26181/19836172.v1.

Slootjes, H. (2025). The perinatal transitions of matrescence: An occupational therapy perspective. In H. Slootjes (Ed.), Enhancing women’s wellbeing during matrescence, motherhood, and perinatal transitions: An evidence-based guide for occupational therapists (pp. 247–274). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003397724-12