This is a bit of a different post from me today. I really want to talk about matrescence and to share a bit about what we’ve included in the textbook to help communicate more about matrescence from an evidence-based perspective.

Matrescence is still in the spotlight! But let’s stop boxing it into the perinatal period and fourth trimester.

So, we know matrescence is not simply a phase around birth. We understand it’s a rite of passage and metamorphosis that unfolds through shifting identities, roles, relationships, resources, bodies, beliefs and power over time (Raphael, 1978). But the desire to anchor back to the perinatal transitions and birth are really strong! So I wanted to use this post to discuss things in a bit more depth.

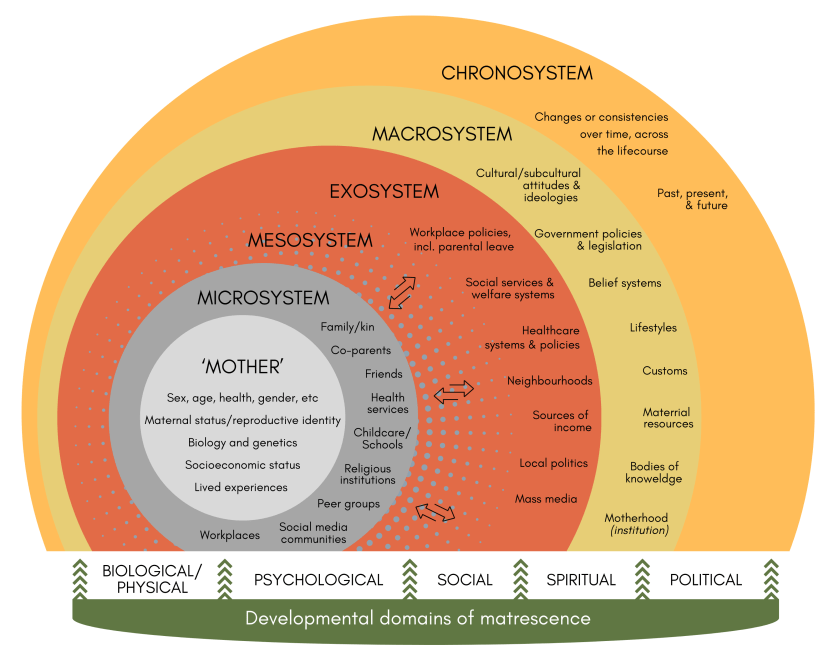

With permission from Routledge (the publisher) to post the figures in colour, we’re going to revisit my textbook chapter with Annie DeRolf, where we locate matrescence within an occupational lens and a bioecological framework to guard against this reductionism. In short, this chapter talks about how mothers’ development is co-created by what they do and the environments that enable or constrain that doing, from the intimate to the structural, across the whole lifespan. It’s basically OT 101. But we’re taking things up a knotch to the next level to help understand matrescence from an human occupational perspective.

The figure, in two paragraphs

The figure above adapts Bronfenbrenner’s (2006) ecology of human development to matrescence. Imagine nested “dolls” – at the centre sits the mother (in this context, bio = person): Her characteristics, capacities, and experiences. Around her are immediate settings (the microsystem), the interactions between those settings (the mesosystem), the systems that shape her indirectly (the exosystem), and the wider cultural, ideological, and institutional forces, including the patriarchal institution of motherhood itself (the macrosystem). All are held in time (the chronosystem), because matrescence unfolds across a lifetime. It’s illustrative, not exhaustive — a living model.

Across these layers, matrescence develops through interwoven domains – not just bio-psycho-social, but also spiritual and political. Hormones and sleep. Identity and mental health. Kinship and work. Digital communities, rites of passage, belonging, policy, money, safety, gendered power. These forces wax and wane across time and intersect across diverse mothering pathways – birth, adoption, fostering, kin and community mothering, and other care roles. Together, these factors intersect and evolve over time to continuously shape girls and women’s health, wellbeing, and quality of life – as gendered beings navigating the culturally nuanced rite of passage of matrescence.

What gets lost when we reduce matrescence to “perinatal”?

- Lifespan context | Mothering is a lifetime occupation and matrescence is a lifelong socialisation process that is culturally bound. The diversity of challenges and meanings associated with navigating mothering roles/identities and motherhood start from the birth of a female child and continue to evolve over time – often spiking again with the onset of menstruation and/or puberty, during perinatal transitions, grandmothering, onset of menopause, and end of life transitions. Collapsing matrescence into a perinatal episode erases these rich cumulative transitions of separation, adaptation, change, and consolidation.

- Structural determinants | Perinatal services rightly focus on mortality and clinical needs, but mother’s wellbeing is also shaped by housing, income, leave, childcare, safety, relationships and psychosocial factors, local politics and cultural ideologies. If matrescence is treated as a clinic-only matter (a health perspective), upstream levers will get ignored (the wellbeing perspective).

- Diverse mothering | There is no universally correct way to mother. Mothering is distinct from parenting or fathers, and not synonymous with motherhood as an institution. Mothering experiences range from joyful to catastrophic. Roles may be shared, non-biological, chosen, or imposed. Narrow perinatal framings can erase (m)others, queer parents, kin-care, and culturally distinct rites of passage.

- Agency and identity | Matrescence is not just something that happens to women in midlife – it’s an ongoing socialisation and practice that deeply culturally nuanced. Matrescence is often characterised by an accumulation of occupations and co-occupations that build – or strip – female agency in relation to motherhood. Reducing matrescence to the perinatal period for screening and symptom management has capacity to strengthen mother-centred care, however overlooks complexity, individuality, meaning, mastery, and power from a lifespan perspective.

A wider, wiser brief for practice and policy

The mother-centred approach suggested by Neely & Reed (2023) can help us to reframe services around mothers’ lived contexts, not just diagnoses – connecting local systems, building parenting skills inclusively, addressing upstream determinants – to fund flexible, equitable support; and investing in real-world “villages”, both face-to-face and digital. This multi-level strategy pairs naturally with the bioecological view in the figure and protects us from siloed, perinatal-only thinking.

So, what can we do now?

First things first. Let’s stop and take a moment to pause and reflect.

- Clinicians and practitioners – Before we reach for diagnostic maps, perhaps we can pause to map the mother’s world. What surrounds her? What sustains or drains her energy each day? The home, the workplace, the care spaces between. The policies that influence her “choices”. The cultural stories that quietly tell her who she should be as a gendered female being in society – or who she has failed to be, and in what way she isn’t meeting sociocultural nuanced expectations as an idealised ‘mother’. When we notice the life stage or phase she’s in, as well as intergenerational and bioecological factors, a fuller picture of her wellbeing needs and challenges begins to emerge.

- Educators and researchers – Maybe it’s time to expand how we hold matrescence in our teaching and inquiry? Not as a chapter tucked into perinatal care, but as a lifelong unfolding – social, cultural, political, spiritual, and deeply occupational. When we frame it this way, we give language and legitimacy to the slow transformations that mothers live long after the baby books end.

- Policymakers and leaders – To truly support mothers, we might begin not with programs, but with the environments that make mothering possible. Safe housing. Paid leave. Affordable childcare. Flexible work. Freedom from violence. Cultural safety and community. These are not extras – they are the ecosystem of matrescence and the gendered context influencing wellbeing determinants.

We can’t change everything, but we can definitely take accountability for our own practices and prioritise an evidence-based perspective that responds to women as human occupational beings.

Matrescence is a gendered human developmental story and a concept developed through anthropological research. From an occupational perspective, we can recognise matrescence is lived through occupations, relationships and structures, across time. When we hold that human occupational breadth, we can understand why we need to hold the perspective that perinatal care can fill one strong chapter without dominating the whole book.

Further reading: This post heavily summarises ideas from our chapter, The occupational nature of matrescence (Slootjes & DeRolf 2025), where we situate matrescence within an occupational and bioecological framework from an evidence-based perspective. Annie and I invite readers to read our chapter and to critically consider how their understanding of matrescence aligns within the nested systems and matrescence development domains in Figure 7.1, and reflect of how mother-centred health promotion can extend beyond perinatal care.

References

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (Vol. 1, pp. 793–828). Wiley.

Neely, E., & Reed, A. (2023). Towards a mother-centred maternal health promotion. Health Promotion International, 38(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daad014

Raphael, D. (1975). Matrescence, becoming a mother: A “new/old” rite de passage. In D. Raphael (Ed.), Being female: Reproduction, power, and change (pp. 65–72). Mouton Publishers

Slootjes, H., & DeRolf, A. (2025). The occupational nature of matrescence. In H. Slootjes (Ed.), Enhancing women’s wellbeing during matrescence, motherhood, and perinatal transitions: An evidence-based guide for occupational therapists (pp. 121–142). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003397724-9